New research funding at PVAMU to support study of Wyatt Chapel Community Cemetery

NEW RESEARCH FUNDING

To support study of Wyatt Chapel Community Cemetery at PVAMU

All photography © Nicholas Hunt, Office for Marketing and Communications, 2024

Through the process, the project hopes to tell more completely the story of the formerly enslaved, buried in the hallowed grounds, and the hardships they endured at the Alta Vista Plantation, where PVAMU stands today.

Historic

&

Abandoned

“This study will explore the African American-lived experience through participatory and archival research, digital humanities, oral history, geospatial data collection and analysis, and the creation of interactive and immersive maps in preparation for the 150th anniversary of PVAMU in 2026,” said Dr. DeWayne Moore, a U.S. and public history professor at PVAMU.

The project was inspired by former PVAMU President Ruth Simmons, who encouraged such studies ‘to affirm to our students that we are awake, that we are concerned for their future, and that we are the Prairie View of our lineage.’”

Dr. Moore said the project is a true community effort, comprising faculty, staff, students, administrators, experts and community members to carry out the research and disseminate the resulting information.

Dr. Moore’s students have conducted interviews with several descendants of those buried in the cemetery. and he hopes that this article will encourage other descendants to reach out and contribute to the project. Due to her strong kinship ties to the University, graduate student Evelyn Todd ’21 is working on the project.

“As a student, you always hear the stories about the cemetery in the back of campus. So, it was sad to find out this was it and watch it go downhill over the years,” said Todd, who is working towards her MBA.

“I wanted to do my part to not just preserve the cemetery but honor it. I’m also really big on learning our history because if we don’t know what we’ve done or where we’ve been, then we won’t know where we’re going.”

‘To Honor Those Who Came Before Us’

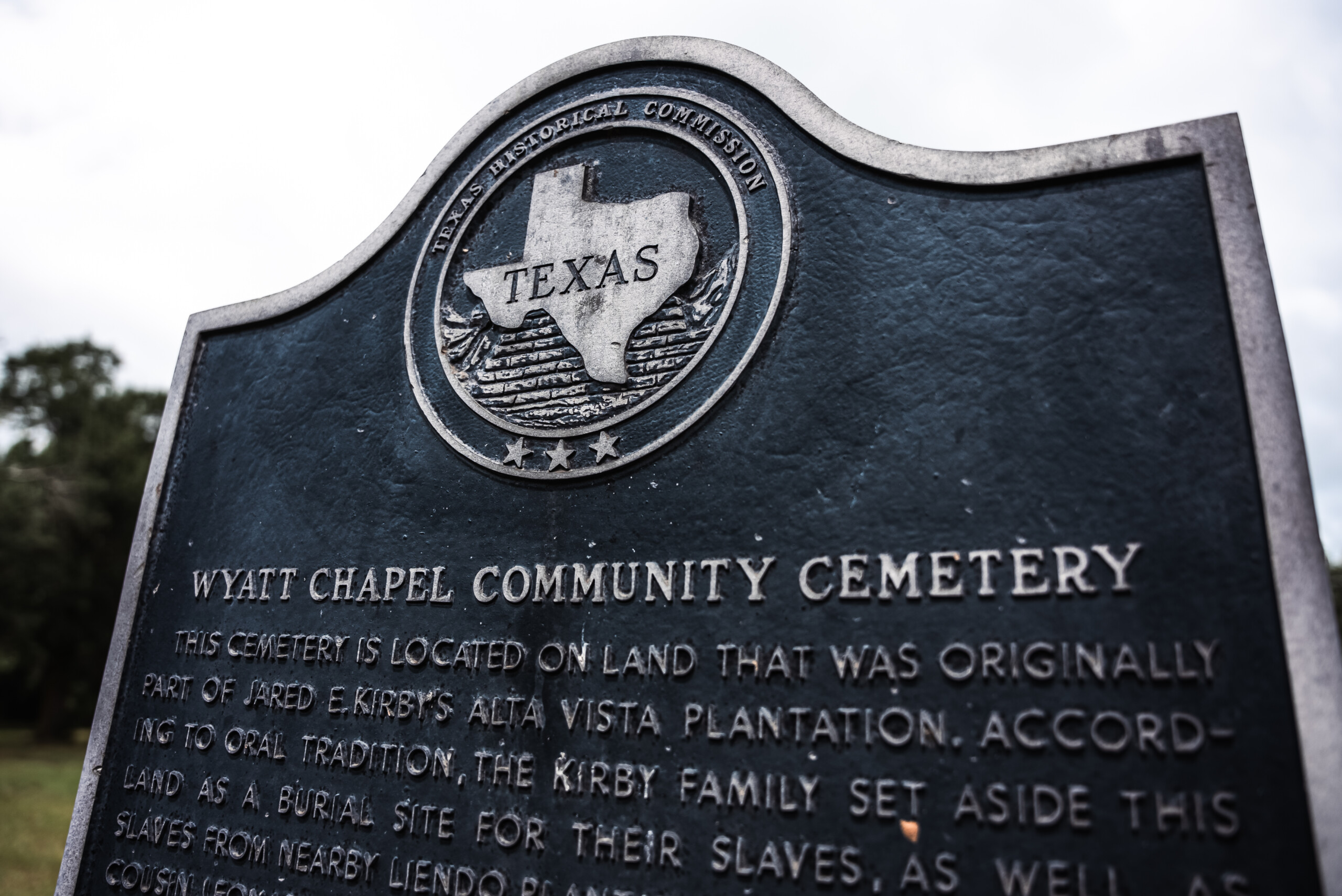

The Alta Vista Plantation, owned by Colonel Jared E. Kirby, became property of the State of Texas in 1876. Kirby’s widow, Helen Marr Swearingen Kirby, deeded the land for the establishment of PVAMU.

Moore said history portrays Kirby as a “benevolent” slaveholder. But that all changed in the summer of 2021 when a June 24, 1936, interview with the only living person known to have been enslaved at Alta Vista surfaced.

According to Moore, Frank Edd White, a graduate student at the University of Texas, interviewed “several of the formerly enslaved in Waller County” near the Hempstead-Bellville highway. Among the interviewees was Elizabeth Burney, who had been enslaved at Alta Vista.

“She had ‘seen negro men beaten until blood ran down their legs,’” said Moore, recounting White’s record of the interview with Burney.

“’Marster Jack,’ as she referred to Kirby, ‘was sho’ mean to his slaves,’ and Burney went on to testify that ‘their food was bad…and sometimes the beef was spoiled and had worms in it, but they were glad to get it and did not complain,’” continued Moore, reading from the Burney interview. “’Their clothes were very scanty at times…Their living quarters were small and overcrowded…There was a great deal of sickness among the slaves, and when they died, a hole was dug, and they were rolled in it and covered up.’”

Moore said the Burney interview offers some of the only information recorded about the burial practices for the enslaved at Alta Vista.

Finding & Saying the Names

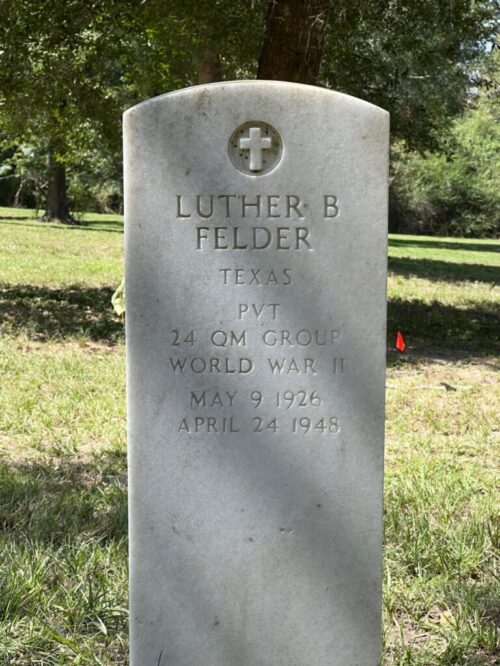

“The cemetery contains a few marked graves, but the names of the internments have proven as elusive as the names of the enslaved at Alta Vista,” he said.

Among those buried at Wyatt Chapel Community Cemetery is Mattie Wyatt Wells, daughter of George W. Wyatt, one of several African American politicians who hailed from Waller County during the Reconstruction era.

“This cemetery contains not only the remains of enslaved men and women who once lived on the enslaved labor farm of Jared E. Kirby, but also the graves of military veterans, the formerly enslaved, and their descendants,” said Moore. “Moreover, this is an important historical site to the descendants of those interred in the cemetery as well as the larger community of Wyatt Chapel and Prairie View. We have an opportunity to invite a host of stakeholders to campus to take part in the research and memorialization process, which can help people reach a consensus about the past and feel more confident about the future.”

Tradition with the Annual Slave Cemetery Trek

To connect students, faculty, and the community with the area’s history, an annual Slave Cemetery Trek was a traditional event at PVAMU that was started in the 1990s by Professor Howard Jones.

However, Moore says the Slave Cemetery Trek has been undertaken by visitors interested in the history of the institution and may become an annual tradition at PVAMU.

“In the past, professors in the Division of Social, Political, and Behavioral Sciences conducted the trek in the fall, including longtime history program director and chair of the Division of Social Sciences, Dr. Ronald Goodwin, whose blog at the Texas Institute for the Preservation of History and Culture is a must-read for anyone interested in connecting the past to the present at PVAMU.”

According to a web page dedicated to the history of Wyatt Chapel Community Cemetery and the ongoing project, the annual Slave Cemetery Trek has garnered strong, emotional reactions from past students who have made the walk.

Some “complained about the distance while others backed away because of fear,” with one student later writing, “There needs to be an understanding that while we are here doing what we are doing, there were others who came before us that worked diligently to produce the opportunities that we have at the present time.”

How to Keep

Track of the Project

and How to Help

Believed to cover approximately three to five acres, the Wyatt Chapel Community Cemetery may hold more than 2,000 graves, said Moore. In the fall of 2023, his team walked the burial ground to conduct a pedestrian survey and identified almost 200 potential grave markers, using remote sensing to determine the size of the burial ground. “Community stakeholders and PVAMU students worked with archaeologists Dr. Nesta Anderson and Melanie Nichols of Legacy Cultural Resources, LLC, to conduct the pedestrian survey of the cemetery,” said Moore.

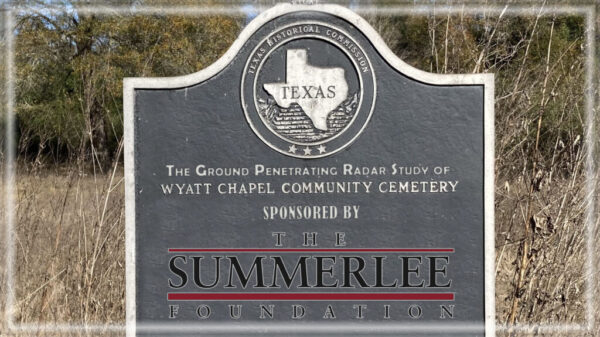

This past spring, Chet Walker of Archeo-Geophysical Associates, LLC, conducted a ground-penetrating radar, magnetometer, and LIDAR survey of the cemetery. “His team is still waiting on the official report from the various studies,” Moore explained.

Donna D. Carter, FAIA, president of Austin, Texas-based architecture firm Carter Design Associates, is also involved in the project as a preservation architect. Her team has worked on multiple historical preservation projects, and they are excited to be part of this one.

In the meantime, Moore and his team built a project website, the Digital PV Panther Project. His students update the blog regularly so everyone on campus and within the community can stay abreast of the latest project news.

In addition to the website, people can also visit the Instagram, X, and Facebook accounts of the Digital PV Panther Project for up-to-date information.

Responsible Public History Practice

“One of the main goals of the project is to demonstrate the value of transparency and responsible practice to public history,” said Moore. “By regularly blogging about our work and posting updates on social media, we hope to inspire a more community-engaged, participatory approach to historic preservation in Texas.”

A review of historical evidence, Moore said, requires a critical eye and a breadth of knowledge sharpened by an investigative spirit willing to look beyond the painted prejudices of the past.

“Primary source materials reflect the perspectives and biases of their authors, and they reflect the systems of power and racist ideologies of the periods in which they were written,” said Moore. “They commodify Black experiences and rarely acknowledge the humanity of enslaved people. The data-driven methods of historical inquiry have often rendered enslaved people nameless; thus, we intend to use qualitative and archival data collections to recover the names and life stories of enslaved people and their descendants.

“We seek to identify as many enslaved people by name as possible, and we intend to represent individual and collective experiences in a self-conscious, responsible frame,” Moore continued. “We plan to compile as much data as possible and employ textual analysis to read against the grain of dehumanizing archival perspectives, and we stand in solidarity with and support descendant communities in telling their own histories.”

![Cemetery Study Team PVAMU students and alumni as well as members of the Waller County Historical Commission and the Prairie View Heritage Committee prepare to begin the survey on October 21, 2023 [Photo © T. DeWayne Moore, 2023]](https://pvpantherproject.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/thumbnail_IMG_2629-1024x768-650x487.jpg)

![A community volunteer searches for unmarked graves A community volunteer searches for unmarked graves [Photo © Evelyn Todd, 2023]](https://pvpantherproject.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/IMG_3682-768x1024-360x480.jpg)

![Nesta Anderson documenting unmarked graves with PVAMU students Nesta Anderson documenting unmarked graves with PVAMU students [Photo © T. DeWayne Moore, 2023]](https://pvpantherproject.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/thumbnail_IMG_2674-1024x768-360x270.jpg)

![Unmarked Graves Rows of possible unmarked graves marked with flags [Photo © Evelyn Todd, 2023]](https://pvpantherproject.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/IMG_3680-768x1024-360x480.jpg)

![Lindsay Boknight Lindsay Boknight looking for unmarked graves during the pedestrian survey on October 21, 2023 [Photo © T. DeWayne Moore, 2023]](https://pvpantherproject.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/thumbnail_IMG_2645-1024x768-360x270.jpg)

![Marking Graves Nesta Anderson and Melanie Nichols explaining to students and alumni the process of recording unmarked burials in a cemetery [Photo © T. DeWayne Moore, 2023]](https://pvpantherproject.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/thumbnail_IMG_2655-1024x768-422x316.jpg)

![thumbnail_IMG_2660 The headstone of Elsie Bailey after initial cleaning with D2 biological solution [Photo © T. DeWayne Moore, 2023]](https://pvpantherproject.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/thumbnail_IMG_2660-768x1024-640x853.jpg)

![thumbnail_IMG_2659 The broken headstone of Albert "Pap" Colling [Photo © T. DeWayne Moore, 2023]](https://pvpantherproject.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/thumbnail_IMG_2659-768x1024-640x853.jpg)

![Luther Felder headstone The military headstone of Luther B. Felder over a year after cleaning with D2 biological solution [Photo © T. DeWayne Moore, 2023]](https://pvpantherproject.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/thumbnail_IMG_2658-768x1024-640x853.jpg)

![thumbnail_IMG_2657 The headstone of Milo Wilson Jr. after the initial cleaning with D2 biological solution [Photo © T. DeWayne Moore, 2023]](https://pvpantherproject.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/thumbnail_IMG_2657-768x1024-640x853.jpg)

![thumbnail_IMG_2679 Melanie Nichols, Gregory Newton, Nesta Anderson, and Sabrina Francis record the last of the unmarked burials in the cemetery [Photo © T. DeWayne Moore, 2023]](https://pvpantherproject.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/thumbnail_IMG_2679.jpg)

![thumbnail_IMG_2654 Gregory Newton leans over to examine one of the many field stones uncovered in the cemetery [Photo © T. DeWayne Moore, 2023]](https://pvpantherproject.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/thumbnail_IMG_2654.jpg)