Gather ’round y’all I got a story to tell

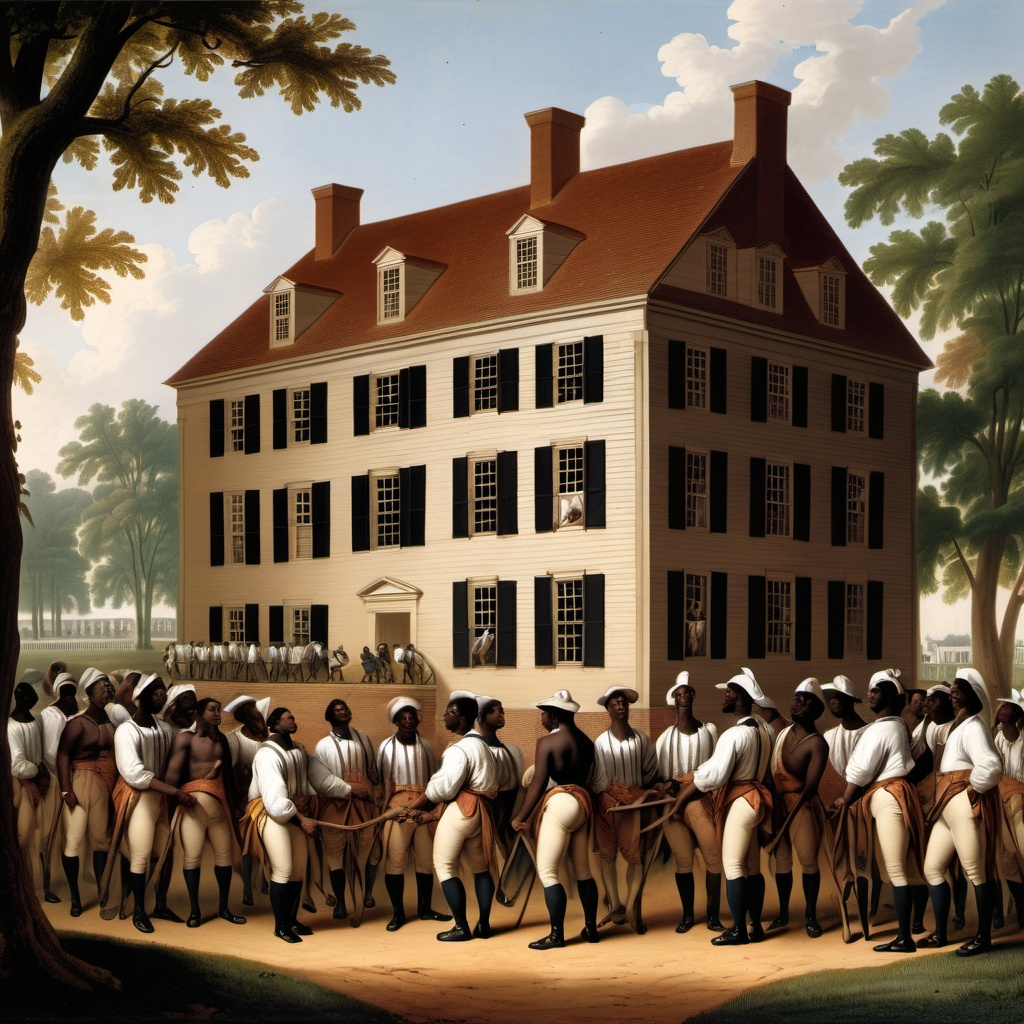

This language frames George Washington’s home as a place of reverence, emphasizing patriotism and hero worship while downplaying its history as an enslaved labor plantation. The term “shrine” influences preservation efforts by prioritizing Washington’s legacy over the experiences of the enslaved people who built and maintained the estate. It shapes interpretation by fostering an idealized narrative that centers on Washington’s leadership, often at the expense of deeper engagement with the realities of slavery. This reverential framing can obscure Mount Vernon’s full historical context, limiting critical discussions on power, labor, and race. While on the topic of language, we can’t forget about oral history and the value it brings. oral history remains invaluable for historic preservation. It captures personal experiences, emotions, and perspectives often absent from official records, particularly for marginalized groups whose voices were historically excluded. Oral testimonies provide insight into daily life, traditions, and cultural memory, enriching historical interpretation beyond written documentation. Even when accounts contain errors or embellishments, they reveal how communities remember and interpret their past, shaping collective identity. In preservation, oral history helps contextualize historic sites, guiding restoration efforts and interpretive programs with firsthand knowledge. It also fosters community engagement, ensuring that local narratives contribute to how history is preserved and presented. By embracing oral history’s subjective nature, preservationists gain a more nuanced, inclusive understanding of the past that written records alone cannot provide. Even though sometimes it can twisted and embellished, it’s hard to ignore what those storytellers experienced through writing. By actually hearing the story or the Oral history, you can be transported back to that time and envision what is going on.

![1850s Mount Vernon A picture of Mt. Vernon in the mid-1800s [Source www.mtvernon.org]](https://pvpantherproject.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/pm-1-web.jpg)

![Mount Vernon 2024 A photograph of Mt. Vernon in 2024 [Source www.mtvernon.org]](https://pvpantherproject.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/dsc_0765-pm-1-web.jpg)

![Historical Records This picture shows two men doing the important work of preserving historical records [AI generated image, 2025]](https://pvpantherproject.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/thumbnail_1C15E307-89C7-4E20-8B50-6D560BB3AE3E.png)