Historical Consciousness and the PV19

Historical Consciousness and the PV19

By Caleb Brookins

You cannot put a price on a good education. Indeed, universities across the nation consider a good understanding of history one of the core sets of knowledge each undergraduate needs to obtain a bachelor’s degree. In my first few weeks working on the Digital PV Panther Project, I have gained access to a vast amount of information, which remains hidden away from researchers, students, and other stakeholders in the dark vault of the PVAMU archives. In my nascent quest to develop archival research skills, I have also gained much more clarity about the importance of the Digital PV Panther Project. By analyzing the events of an important, yet understudied, chapter of local voting rights history, this blog post demonstrates that historical understanding is necessary to achieve a heightened state of consciousness. This is the story of the PV 19.

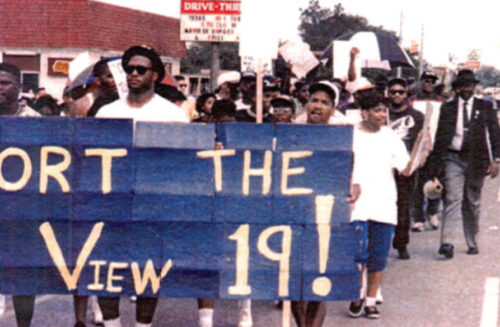

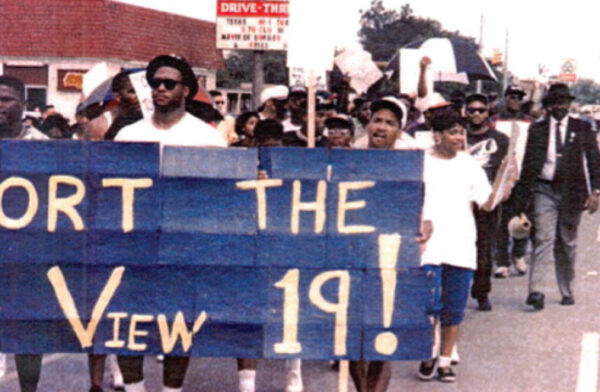

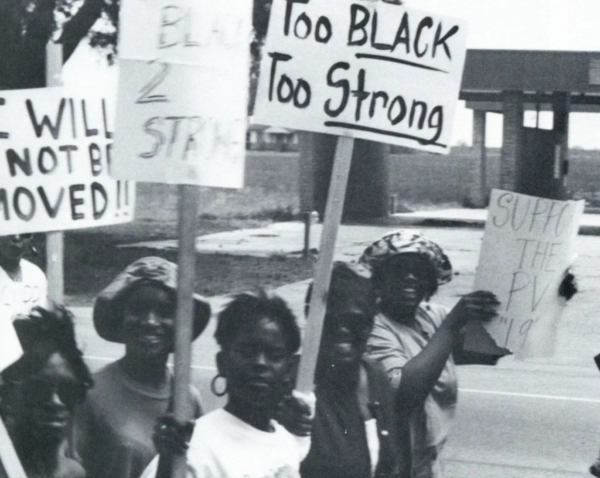

Prairie View A&M students protest the county district attorney’s attempts to prosecute their fellow students for voter fraud in 1992.

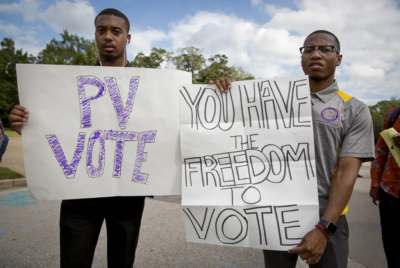

(Left) Brizjon Wilright and Kendric Jones held signs outside the Willie A. Tempton Student Center at Prairie View A&M to encourage other students to vote in 2016

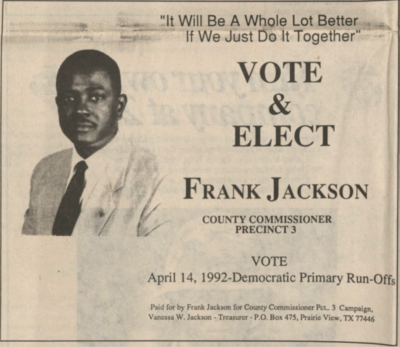

The Prairie View Panther, April 1992.

Voting is crucial in a healthy democracy. Whether it’s a national, state, or local election, the significance of high voter turnout cannot be stressed enough. In 1928, Democratic Party Presidential Candidate Al Smith openly appealed to Black voters during his failed bid for the presidency. Since the Civil War, African Americans had aligned politically with the Party of Lincoln, the Republican Party, due to its core stance on abolishing slavery. During World War I, however, the Great Migration of African Americans out of the Jim Crow South created large voting blocs in several northern states, and the Democratic Party began to covet the Black vote in key swing states by appealing to the interests of African Americans.

African American’s love affair with the Democratic Party reached a milestone with the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which brought an end to the disfranchisement of African Americans on the national and state level. The number of registered Black voters rose significantly, and conservatives in power have attempted to dilute their voting strength in numerous ways ever since. In Waller County, Texas, for example, the students attending Prairie View A&M University repeatedly find themselves in the middle of an ongoing fight for the very soul of democracy.

Prairie View A&M students protest the county district attorney’s attempts to prosecute their fellow students for voter fraud in 1992.

“A horsewhipping is what Frank Jackson needs,” argued Texas Advocate editor Mary Levy in mid-1992, “for misconstruing the facts to the media and, most importantly, to the students.” Having won the Democratic primary against Richard Frey (votes: 782 to 475), Frank Jackson faced Republican Ron Leverett for the seat of Waller County Commissioner in November 1992, and his campaign received national attention due to his support for 19 PVAMU students, who had been indicted locally for aggravated perjury and illegal voting.

In the spring of 1992, a host of PVAMU students had filled out registration cards during a voter registration drive, assumed they had concluded the process, and with confidence proceeded to vote. When their names did not appear on the registration roll, they signed affidavits stating that they were registered to vote. The voter registration office subsequently notified Assistant Waller County District Attorney A.M. “Buddy” McCaig. On March 26, 1992, he filed indictments against twenty-three individuals for aggravated perjury and illegal voting, and he issued subpoenas for them to appear before grand jury on April 2nd.

Prairie View A&M students protest the county district attorney’s attempts to prosecute their fellow students for voter fraud in 1992.

The April 1992 March on Hempstead

Comparing it to the March on Washington, Prairie View Panther Editor-In-Chief Michell Johnson reported that “hundreds of students walked and drove caravan-style to Hempstead…accompanied by the Prairie View police, a fire truck carrying refreshments for the demonstrators and an ambulance for those who could not endure the heat…Many students armed with their voter registration cards lined up to exercise their right to vote. “It felt good,” admitted one student, “to be part of a unified effort to improve the rights of students at Prairie View.”

No one has ever questioned the rights of students at the University of Houston or Texas A&M to vote, but the issue is constantly raised about the students who attend PVAMU. Since the 1880s, voting boundaries in Waller County had split up the vote in the predominantly Black communities and given citizens little voice in government. Hempstead was divided into two voting precincts and Prairie View was divided into three. Students were forced to vote at two separate locations depending on which side of the campus they lived.

As a result of the 1980 census, however, the county was redistricted to maintain an equal number of voters in each precinct. Federally required redistricting of the voting precincts in Waller County gave Prairie View and the surrounding community a substantial amount of voting power. At long last, Waller County would have a representative government in 1992.

Of the 23,390 population, 11,993 were white, 8,609 were black and the rest were Hispanic or Asian. Fear struck deep in the hearts of the majority.

The Prairie View Panther featured a regular section called “Speak Out!,” which provided students a space to publicly voice their criticisms. In the April 3, 1992 edition, one of the PV19, Donna Shelton, took the opportunity to comment on her indictment as well as the impact on local politics.

As one of the 19 students who are being falsely accused of registration fraud, by the Waller County D.A, Albert “Buddy” McCaig, I feel that it is time for me to speak out!

Acting within the Constitution and exercising our right to vote, I, we were brought up on criminal charges. These charges hold penalties of two to ten years in prison, fines, or probation.

This is ludicrous. I feel that this is a ploy used by our enemies in the Waller county D.A’s office to harass and discourage Prairie View student from voting. Do you realize that there are over 5,000 students at P.V., and that if we acted as a whole, we could have an immeasurable impact on Waller county? Well I do, and I hope that you don’t let this infringement on our voting rights go unchallenged.

As students, in the past we have not been going to the polls enough. However, thanks to the strong leadership of the SGA and the extended P.V. family, who have been persistent in the struggle for students to be able to participate in the political system. But now we are now being discouraged from exercising our franchise. say to all P.V students, don’t let this incident stop you from doing the right thing, empower yourselves. If you are not registered, then do so, it is your right.

I would like to thank Mr. Frank Jackson, who has been at the forefront of this struggle, and I would also like to thank the entire Prairie View student body for being behind the P.V.19!

The fight is not over, we have been indicted. Just remember that if we don’t I take a stand today, there may not be a chance to do so in the future. The run-off elections are April 14 “We’re proud and we’re Black, and we ain’t going down like that!

Reflecting the increasingly frequent, unsubstantiated claims of voter fraud since 2016, the published response of Waller County district attorney McCaig in the Prairie View Panther demonstrates his efforts to dissuade PVAMU students from voting. In the open letter, which he asked be printed in its entirety, McCaig admitted to receiving a “great outpouring of support from many of the permanent citizens of Waller County,” most of whom did not “want their legally cast votes to be diluted by someone who is not a legal voter.” Attacking the 1979 SCOTUS decision in Symm v. United States, which allowed college students to vote where they attended school, McCaig argued, “it’s bad enough being forced to accept the fact that transient students living in a dormitory for a couple of semesters, paying no property taxes, have a right to vote in Waller County (when they should be voting at home) without having county citizens put up with illegal voting on top of that.”

No evidence of voter fraud has come to light to substantiate claims since 2016, and no evidence of illegal voting came to light in 1992. The PV19 were the victims of voter suppression tactics, and the same tactics have been resurrected since 2016 to suppress the voting rights of minorities. By examining the digital resources available about the PV19 and analyzing them in light of contemporary voter suppression efforts, this blog post has made clear that a better understanding of history is crucial to making confident political decisions. Consider where PVAMU is located and the history behind it. If we really put everything in perspective by stepping back and acknowledging the past, it is not difficult or far-fetched to see the prejudice oozing out of the county. In closing, I want to reiterate Donna Shelton’s call to action, which still rings true today:

We are now being discouraged from exercising our franchise [but] don’t let this incident stop you from doing the right thing, empower yourselves. If you are not registered, then do so, it is your right…We’re proud and we’re Black, and we ain’t going down like that!

Notes:

Albert M. McCaig, “McCaig on the PV 19,” The Prairie View Panther 69:7 May 1, 1992, p.7.

Donna Shelton, “Speak Out! One of the ‘PV 19’ Speaks to Voters,” The Prairie View Panther 69:5 (April 3, 1992), p.1.]

Morenike Efuntade, “Prairie View is in New Precinct,” The Prairie View Panther 68:17 September 27, 1991, p.1.