“Silence is a Very Good Weapon”

“Silence is a very good weapon”

By Malachi McMahon and T. DeWayne Moore

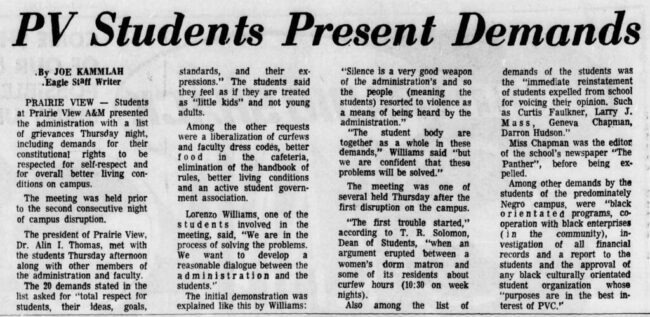

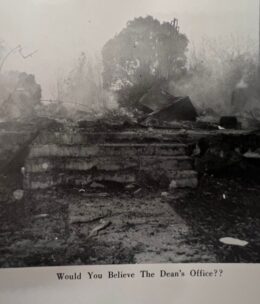

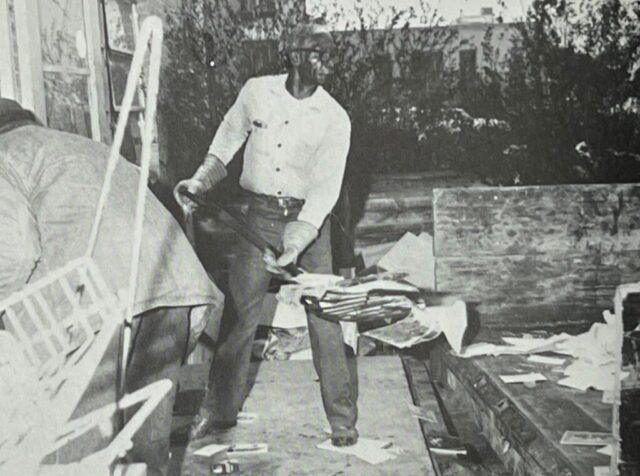

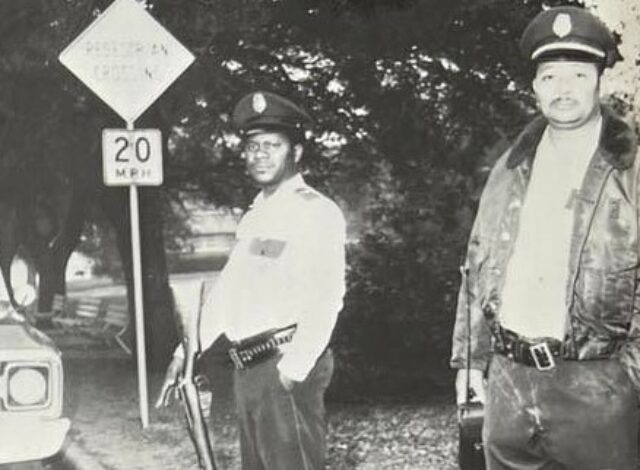

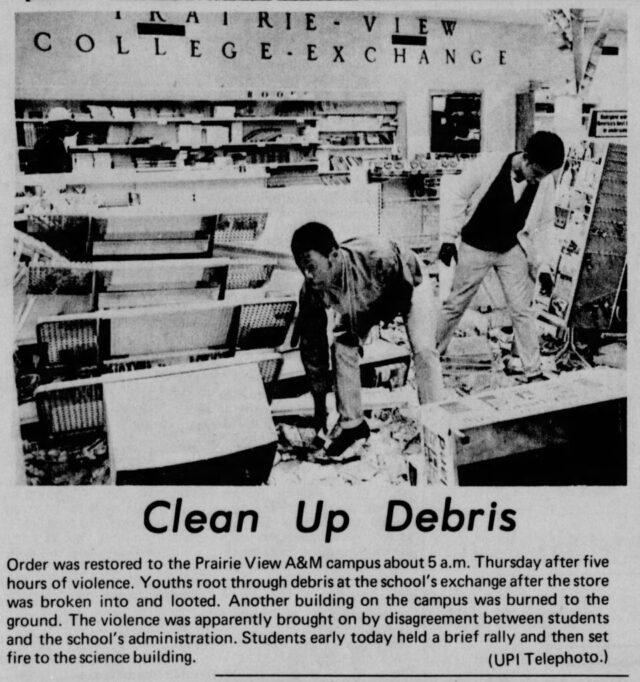

“Silence is a very good weapon of the administration,” argued Lorenzo Williams, one of the students who met with PVAMU President A.I. Thomas in late February 1971, “and so the people (meaning the students) turned to violence as a means of being heard by the administration.” The meeting took place on Friday, February 26, two days after an estimated 1,000 PVAMU students marched to his home and presented him with a list of 19 demands, including his resignation. President Thomas refused to bow immediately to the demands, however, arguing that he did not feel that he should reply to any “demands under threat, coercion, intimidation or disruption,” and the students proceeded to destroy over $200,000 of property on campus. After leaving his home on Wednesday evening, the students burned down the campus security building, the Dean of Men’s offices, and the Office of Freshman Studies. They overturned a security patrol car and set it on fire, and they broke into and looted the College Exchange Store. On Thursday morning, the students set fire to the Army ROTC building and smashed windows in several dormitories.

In a subsequent issue of the newsletter for parents of students, The Guardian, he agreed to “discuss any issues of concern to our students provided they are presented in an orderly manner by appropriate student representatives,” and the March 1971 issue of the Prairie View Panther contained a list of demands and replies by the administration (Click HERE for the primary source). It also contained an article titled, “Academic Life Back to Normal Again,” which diminished the problems that gave rise to the protest and highlighted the administration’s decision to deny 127 students readmission for their participation in the protest.

One of the students denied readmission was Lawrence Tureaud (aka Mr. T), who served as the Vice President of the Freshman Class.

The student uprising in February 1971 stemmed from a host of problems on campus, and the students later submitted a list of 19 demands to President Thomas. (Click HERE to read a list of all 19 demands and replies by the administration). Yet, a few specific developments in mid-February sparked the outbreak of violence. PVAMU tightened its shoplifting policies at the Campus Exchange Store, a policy which led to more serious punishments for anyone caught stealing, and the university also expelled an estimated 200 students for failing to maintain a good grade point average. Several of the students were members of a group called People for Afro-American Life, an organization that published an underground newspaper and had previously been banned on campus (See the (Tyler, TX) Morning Telegraph, February 26, 1971).

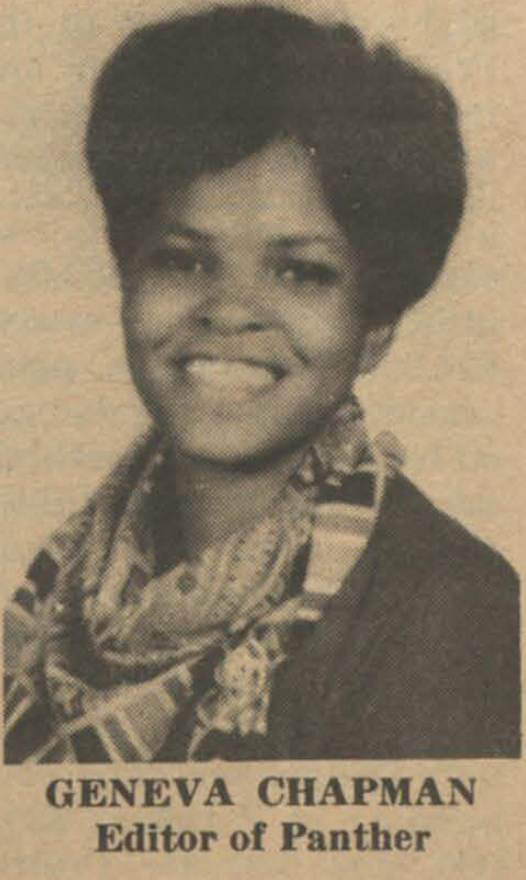

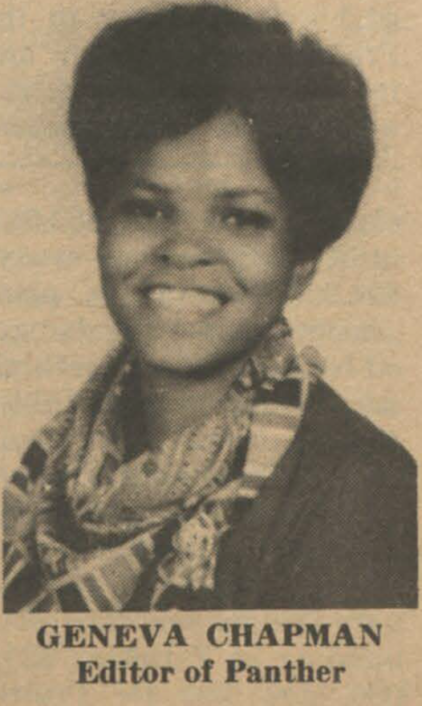

Moreover, and perhaps most importantly, the university decided to expel Geneva Chapman, the outspoken editor of the student newspaper, The Prairie View Panther, who had defied the gendered dorm policies, which prevented female students from leaving campus on the weekends. On the weekend of February 20-21, she travelled to New Orleans to celebrate Mardi Gras, and the university’s decision to expel her the following week gave rise to the student protests.

Several of the demands, such as the resignation of President Thomas, an extension of women’s curfew, better food on campus, and the return of all expelled students, pertained to longstanding problems on PVAMU campus, but others–such as calling for an end to the ROTC training program on campus–reflected the Anti-Vietnam War protests that had erupted on college campuses across the country.

Out of over one thousand protesters, the police arrested only two students involved in the uprising–20 year-old junior Leonard Baker and 28 year-old Air Force veteran Quincy Brooks were charged with acting to promote damage to school property. The judge set the two men’s bond at $100,000 each–an extremely large amount of money in 1971 that might be over a million dollars today. Waller County Sheriff Jimmy Whitworth told one Houston Chronicle reporter that he could not recall another misdemeanor charge with so high a bond. The attorney defending the two students claimed that the arrests were “based on that old logic of 20 years ago – you get the leaders and kill the protest.”

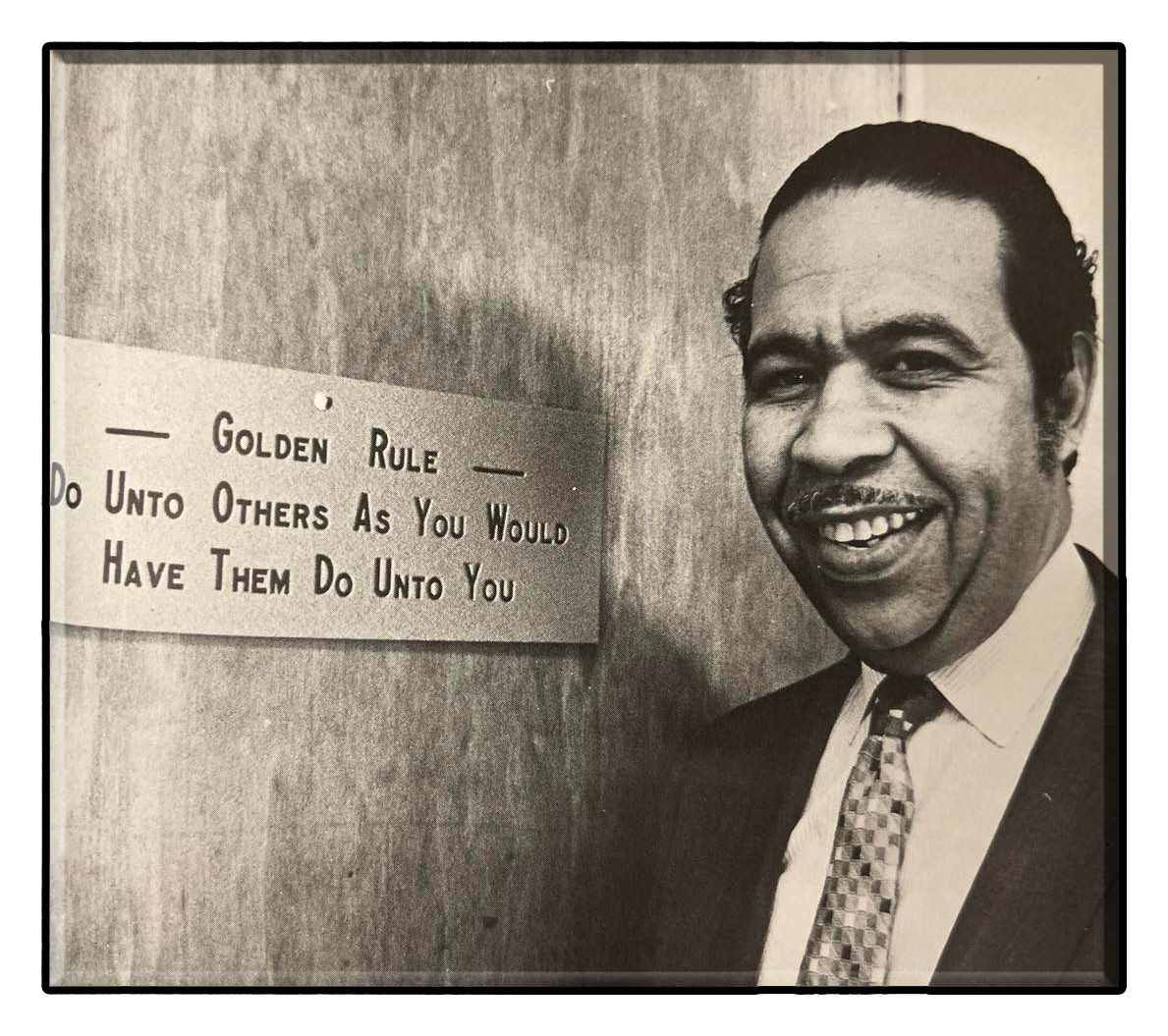

PVAMU President A.I. Thomas later blamed the protests on a couple of “real professional agitators.”

President Thomas declared that “real professional agitators” came from elsewhere to Prairie View with the intention to stir up trouble on an otherwise harmonious, peaceful institution of higher learning.

“troublemakers”

PVAMU President A.I. Thomas’s claims not only invoked the charges of white supremacists who sought to delegitimize the protests of African Americans during the Civil Rights Movement, but they also reflect the contemporary political tactics of conservatives since the murder of George Floyd, who sought to delegitimize the marches, protests, and other acts of civil disobedience that erupted in Minneapolis, Minnesota and Portland, Oregon–among many other cities across the country. Conservative political pundits refused to admit that police brutality and other problems with the criminal justice system developed directly out of racial inequality in America. Instead, they blamed paid professional agitators, specifically members of a mysterious group called ANTIFA, for creating civil unrest across the country.

President Thomas shut down the momentum of a potentially powerful movement by adopting the same tactics used by administrators at Tuskegee University in 1968. He closed PVAMU campus indefinitely in March and dismissed the entire student body. Despite his claims that “real professional agitators” were responsible for the student uprising, he attempted to weed out the student organizers by forcing every single student to re-apply for admission. The students, however, did not have to re-register for classes. They simply picked up cards that allowed them to come back onto campus and classes resumed where they had left off when the school was closed.

PVAMU was established on top of a former slave labor plantation known as Rock Island place, or Alta Vista. In 1876, the state bought it and turned into a land grant school for African Americans. The plantation may have been transformed into a college campus, but students and faculty told one reporter in the early 1970s that “a plantation mentality” lingered on at PVAMU–“complete with the endemic suspicion, fear and intrigue that once existed between” house servants and field workers.

Unlike in 1968 at Tuskegee, where a court injunction reinstated expelled student activists, the 127 students denied re-admission to PVAMU–as well as the estimated 200 students expelled in early February–never got the chance to finish their degrees on “The Hill.” Despite serving as the editor of the student newspaper for more than two years, Geneva Chapman never again roamed “The Hill” where she had so passionately and fearlessly editorialized about her experiences as a Black woman during the tumultuous late 1960s. Unfortunately she passed away recently, and we never got the chance to make a case to have her re-instated. To read more about the work of Geneva Chapman for the Prairie View Panther, please click HERE to search the digitally archived student newspapers in the John B. Coleman Library.