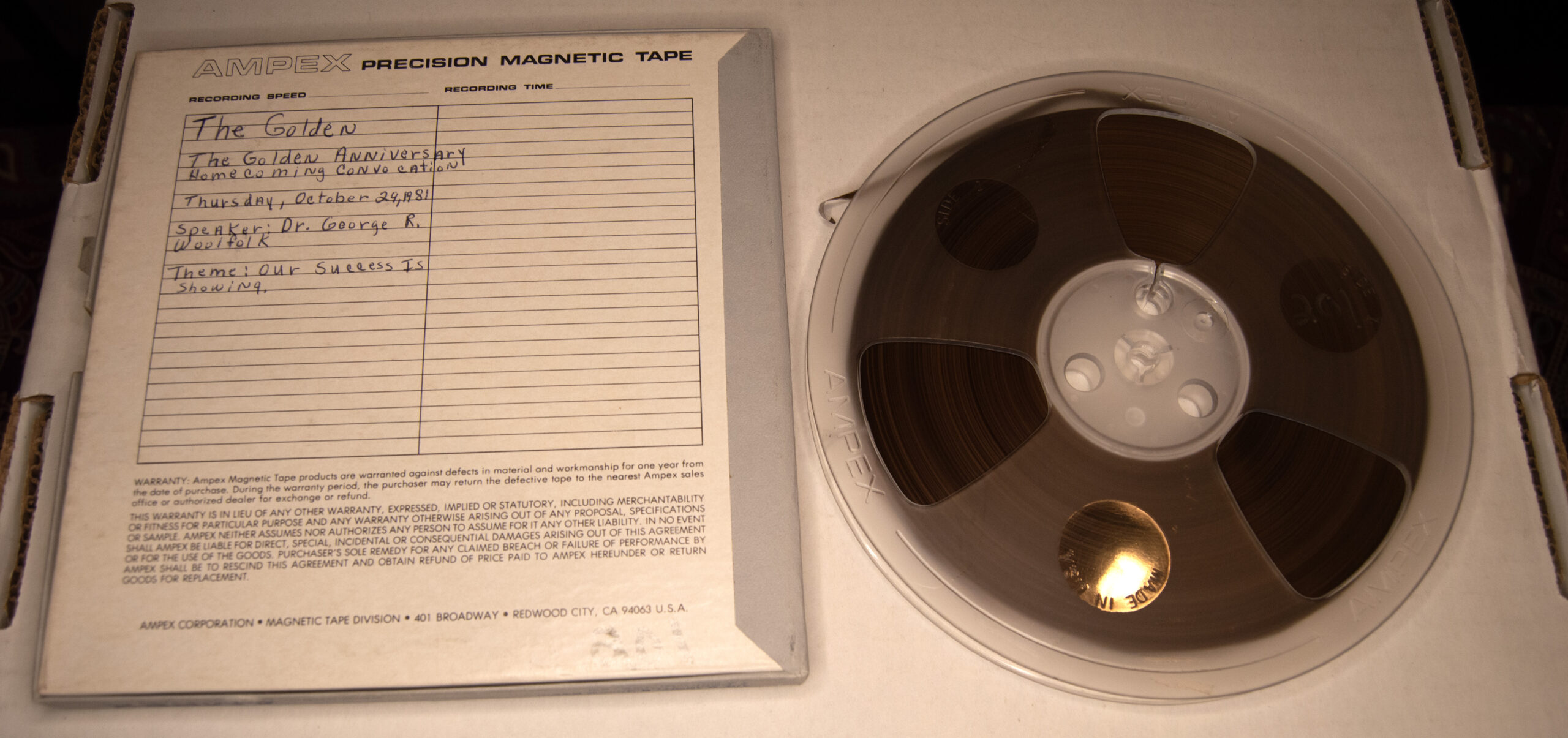

Analog tape digitized by Michael Lee at Rare Records in Winchester, TN in Fall 2022

Digital audio transferred from the Google Drive to Microsoft Teams by Lindsay Boknight on February 10, 2023

Edited by Jaylynn Brantley on November 10, 2023

Edited and Curated by T. DeWayne Moore on November 12, 2023

LINK to the 1981 Convocation Program

Alice Clemons, Miss Prairie View 1981-1982, delivers the introduction of Dr. Woolfolk.

Thank you, ladies and gentlemen. It is my pleasure to introduce our speaker for the occasion. I know the speaker was born, raised, and educated in Louisville, Kentucky. He earned the Bachelor of Arts degree in History from Louisville Municipal College and the University of Louisville, the Master of Arts in History from Ohio State University, and the Doctor of Philosophy in History from the University of Wisconsin.

This learned historian is a member of the Executive Council of the Association for the Study of Afro-American Life and History, a member of the Board of Editors of The Journal of Negro History, a member of the Executive Council of the Texas State Historical Association, the technical advisor to the Waller County Historical Commission and vice chairman of the American Revolution Bicentennial Commission of Texas. I could go on and on with his many professional involvements, but [I] would like to mention a few of his publications.

Included among his numerous publications are “Cotton, Capitalism, and Slave Labor in Texas” in the Southwestern Social Science Quarterly, June 1956; “Taxes and Slavery in the Antebellum South,” in the Journal of Southern History, May 1960; “Social Literacy, the Social Studies, and Negro Youth,” in The Texas Standard, June 1962; “And The Word Became Flesh,” in The Journal of Negro History, Spring 1966; a book entitled The Free Negro in Texas 1836-1890, published in 1976, and perhaps his most special treatise, published in 1962. Prairie View: A Study in Public Conscience, 1878-1946.

Our illustrious speaker, who is married to the former Douglas G. Perry, has one son, George Jr. At this time, I take great pride in presenting to you the chairman of the History program at Prairie View and an outstanding member of the Prairie View family since 1943, our speaker Dr. George Ruble Woolfolk.

[Pause for applause]

At 3 minutes and 3 seconds, Dr. Woolfolk begins his address:

I’d like to speak briefly this morning on the general subject, “Prairie View: A Success Story,” in keeping with the theme of the golden anniversary for this year. At the homecoming convocation, it is fitting that we review the accomplishments of this institution.

It is [fitting that we] take pride in its development, in what it has done, and how our students have contributed to the great development of the state, nation, and their particular localities. I said in some writing a few years ago, in thinking about the institution:

One hundred years is a long span in the life of a man or an institution. What do the years mean? For a man or an institution; if they are filled with the honest sweat of service to humanity–with the patient following of that higher law of unflinching fidelity to the dictates of a calling–the years are a benediction.

Prairie View is an institution. A public institution. But an institution is an empty thing without the beating hearts and the yearning souls of mortal men. And down the 100 years of Prairie View’s existence, men have lived and dreamed here until every blade of grass and every rock, in that wise primordial way in which the primitive earth knows and cares, has joined the choir invisible to bless their memory. For every man whose foot has touched his hallowed soil has found his spirit and has broadened and deepened it until what started out as an ambitionless meandering stream has become a purposeful river upon whose tide, now turbulent, now tranquil, floats the destiny of countless hopes and dreams.

The spirit of an institution is a compound of many things—a strange and often quixotic amalgam of unrelated, sometimes contradictory, elements. Founded, symbolically, upon the ruins of the slave plantation, this university was authorized in the spirit of fair play of the Constitutional Convention of 1876, where wisdom would not allow vengeance to triumph over justice. The men of the parent school at College Station, growing ever wiser with the years, have translated the sense of justice into an ever-broadening channel. The humble student—from every nook and cranny in the land—has left the echo of his laughter upon the wind. His hopes within the lurking shadows of our halls and byways.

The giants [and] the world shakers have stood on our hill to mingle their search for truth with the fledging hopes for life. And men of dedication have worked here–worked to bring a new heaven and a new earth often with only faith and their hands–often without the spiritual and material compensation that their sacrifices merited–but always with a sense of mission–with a sense that somehow, someway, time would reward their efforts–would give to those to whom they had given their minds the victory of a new world–of an enlightened society.

And it is within the context of that quotation, which I wrote several years ago, that we would like to cast the evaluation of this Golden Anniversary Convocation. Because in it is to be seen the true thrust of the meaning of an institution, which is evaluated in spiritual terms, terms of the minds and the hearts of those who dream of it, who bring to it their vision and their awareness.

We have been very fortunate here in the dreams of the leadership of the men who have headed this institution. There have not been many. Some have been of long duration. But all of them had within their heart and their mind some concept of what our people might become, and we pay tribute to them today. Because those who will be returning over the next few days are a living memory of what they dreamed. They bear in their bodies the mark of those dreams.

Though L.W. Minor was not here long, he was the first of the dreamers. He opened the school in the plantation house. And here on Kirby’s acres, they planted the seed. And the two Anderson brothers. One [E.H. Anderson] died soon. L.C. [Anderson] dreamed of an institution that would lead…the leaders, the Black leaders of this state in a consortium of educational men, who would bring to bear their strength in the uplift of their people. He created the state teachers, the Black State Teachers Association. And he gave a long arm to the institution. He would leave here and go on to Austin, where they named Anderson High School in Austin for him. And his name is Laurine. Our Anderson Hall is named for him.

And then came our Edward Lavoisier Blackshear. The immortal Blackshear. Dreaming the Tuskegee dream. Are the people capable, strong, able because they could come to grips with economic realities of poverty and lack of opportunity? Blackshear wrought well and was well-loved.

And then [came] John Granville Osborne, who created the four-year college here. His tenure was short. But for the first time, this institution operated under his management as a college institution. And I told his family that were here for the last convocation in the spring, how fortunate they were to join in the continuing recognition here on this path of their relatives. It made such a signal contribution to the ongoing of this institution. His was a great dream. He dreamed of medical schools here. He was a medical man. He brought the hospital here. He brought the nursing program here. He brought the four-year college here. His was a dream of excellence, and his was the dream of total service.

And then he was followed by that tall, gaunt, determined man, William Willett Rutherford Banks, who claimed that the entire state of Texas was his campus. And whose motto, “Prairie View serves Texas,” became the byword. Who served…who sought to serve every need. Was it medical? Was it educational Was it spiritual? Whatever. Come to Prairie View. We will be the focal point of your program. Was it research? The first fledging research program merging as a dimension of the black educational ethos began with the Banks administration.

And then, of course, he was followed by another dreamer, Edward Bertram Evans, who carried the institution into the international realm…who himself personified what it meant to serve on the world scene. Recognized by both the federal government and the United Nations as an authority competent to operate in the international arena and to advise both in Africa and the [Middle East], he became a symbol of excellence in a period when Prairie View became the symbol of world significance.

We have never retreated from that position.

His successor, Alvin I. Thomas, has not retreated from that position. He dreams larger dreams than have ever been dreamed before on this campus—a dream of first class…of joining the mainstream of American life. He dreams beyond all dreams, a dream that has no limits of race, of color, of creed. This president has dared the lightning by dreaming a dream that says Black men have no limit, have no boundary. Black men have no barrier. We shall turn this institution into a place and into a situation where the world…and the concerns of the world, and the occupations of the world will be its concerns and its infancy.

And so all of the men who have headed the school have been pioneers. They have been a step ahead of the awareness of their people. They have dreamed for their people. Dreamed great dreams. Great thoughts. And those who come back, they come back to dreamland, and that truly is the function of an institution of higher learning. It is the place of dreams. Because the scriptures have truly said, “Without a vision, the people perish.” And, of course, Prairie View is a success story because the university continues to expand its interest in research. I dare say, from these fledgling days of the Banks administration, the administration of Dr. Thomas has emphasized strongly experimentation, research…both sponsored research by government and by foundation as a part of the normal program and the normal dimension of the institution of higher learning. Where we used to receive pittance, now we receive millions of dollars for research.

Because without the money to stimulate the mind of researchers, without the inquiring mind, an institution is sterile. Without the inquiring mind, an institution has nothing to put back into the stream of knowledge to justify its existence. Without the inquiring mind that can produce both theoretical and functional knowledge, an institution does not live.

And then we continue to contribute to society. We now know that we must stay on the frontier of opportunity for our people. If we will, if we ought to escape that peculiar position of becoming the underclass, where there are no job opportunities for our people at all, we must continue to pioneer in the economic arena. Opening more doors, expanding minority opportunity into new areas of opportunity. And we go forward now in the areas of engineering and the other new technological fields that are opening for Black people, and we must continue to go forward in these areas if we ought to, ought to keep abreast all the time, and to keep young black men and women alive and alert. If we do not pledge ourselves to continue our contribution of graduates both to our traditional areas and to new areas, we will die. The question of what we will do—our functional significant—will be settled.

So there is something fitting, therefore, in the fact that after 100 years or more, we are the university is returning to the full realization of its founding as an agricultural and mechanical emphasis. We are now operating in instructional areas, which the system to which we attach [had] better understand, admissions of the two institutions now coincide more and more with the better concern for creativity and knowledge than we had before. We have come from a small fledgling institution to a modern university with concerns which are worldwide.

We enter our 2nd century in this Golden Anniversary with a deep concern for our nation. And we hope those who come back to us for this convocation do the same. And we are also aware that we have a debt to our people, but our success is imperative. We must be a success because we serve Black youth and Black youth will only understand the success of Black men. We must be a success here, because our success is necessary. In the concept of success—as all youth know what success is—we must furnish the role model, because Black youth can understand the success of Black men. And to that success, we commend you. We are proud of the heritage of the success at this institution.

On this golden convocation, on this golden convocation anniversary, we present to those who come back to us a pride, a continuing pride in achievement, a heritage which they can come back and bask in the glory of, confident that their institution has a continuity, a purpose, and a function that will never die.