Prairie View A&M University (PVAMU), the first public supported historically black university (HBCU) in Texas, was established on Alta Vista, the former enslaved labor camp of Colonel Jared Ellison Kirby, who, in 1860, after a decade of steady accumulation, had perhaps become the wealthiest resident in then-Austin County. Just before the Civil War, Kirby owned more than 8,000 acres worth $285,000, and $175,000 in personal property, including 139 enslaved men and women. According to oral tradition, Kirby set aside some land as a burial site for the enslaved from both Alta Vista and Liendo, an enslaved labor camp owned by Kirby's cousin, Leonard Waller Groce. Hundreds of unmarked graves on the edge of campus are believed to date to the antebellum period, but African Americans continued to use the cemetery after Kirby's widow, Helen Marr Swearingen Kirby, deeded the land to the state in 1876 for the establishment of PVAMU.

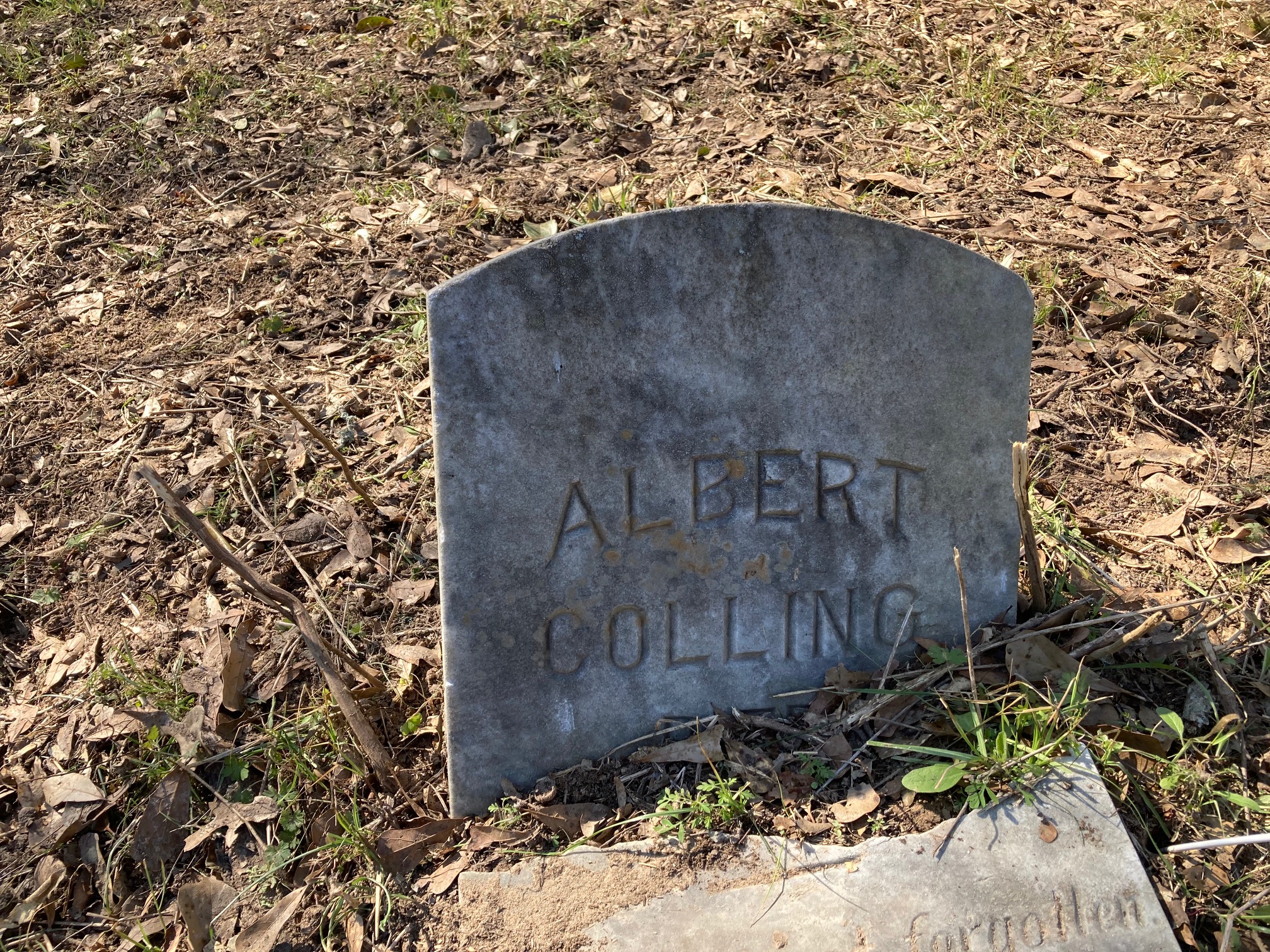

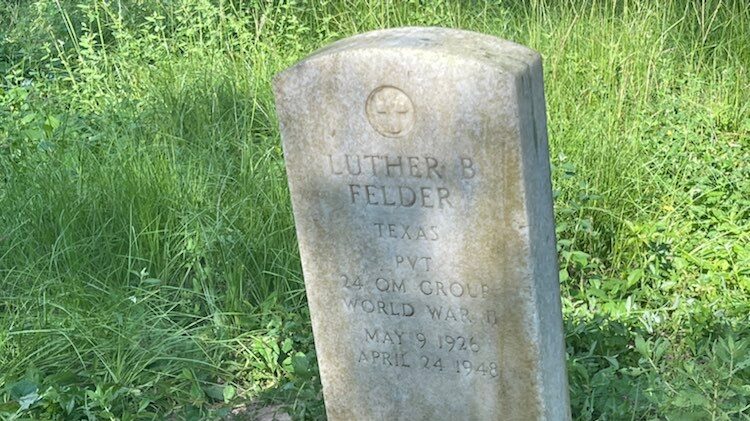

The burial ground became associated with and named for Wyatt Chapel, a nearby African American church. Based on slave schedules, Wyatt Chapel Community Cemetery might contain the graves of over 2,000 of the enslaved, formerly enslaved, descendants of the enslaved, and other itinerant workers. No one made a formal record of these burials, however, and the historic burial ground, which is located behind University Village Phase III, was over time abandoned, especially after 1961, with the establishment of nearby Prairie View Memorial Gardens. While the cemetery contains only a handful of marked graves, we have recently discovered a host of death certificates that prove the cemetery contains veterans of World Wars I and II, former slaves and their descendants, and local pastor George W. Wyatt, who represented Waller County in the state legislature in the 1880s.

In the early 1990s, the state of Texas erected a historical marker on the road closest to the cemetery, but the site became conspicuous for the dumping of trash and non-disposable debris leading up to the summer of 2007, when participants in a graduate course at Rice University and PVAMU acquired global positioning systems and ground-penetrating radar to prove that such equipment could be used to locate lost graves. Over the next few years, graduate students from Rice University followed up on these efforts and noted hundreds of "anomalies" on the surface of the ground. Yet, Rice did not complete their study of the cemetery, and many questions remain about the actual boundaries of the burial ground as well as the number of internments on site.

By hiring a remote sensing firm to conduct an archaeological study of Wyatt Chapel Community Cemetery, and by inviting landscape architect Azzurra Cox to develop a landscape design concept for a memorial park and outdoor history museum, this grant project will provide the foundations for many future student-engaged public history projects and reparative justice initiatives at PVAMU.

For a list of all members of the project team, please click HERE

To examine the project schedule in detail, please click HERE

A Case for Study and Memorialization

How does it benefit the community?

by T. DeWayne Moore

From the mid-1990s to the early 2000s, the Annual Slave Cemetery Trek—hosted by the Division of Social Work, Behavioral and Political Science and covered in the student newspaper, The Prairie View Panther—made sure that students at Prairie View A&M University learned about Wyatt Chapel Community Cemetery and the institutional history of the university.

Dr. Howard Jones and Dr. Kevin Washington led groups of students to the slave cemetery “on a journey into history and a journey into the spirit,” and they explained:

there are men buried here who had their testicles cut off as punishment for attempting to procreate with the women. There are women buried here who were raped and beaten by the slave master and were not allowed to refuse his seed.

According to Prairie View Panther reporter Tony Browne, “the students realized the pain and suffering that our ancestors went through as they stood in the presence of the many graves of men, women, and children. A variety of tombstones, crude markers and sunken-in areas of earth are silent reminders of the agony, torment, anguish, and nauseating misery that our forefathers and mothers endured, in hopes that we would live a better life.

The old burial ground, which sits on the backside of campus, is perhaps our oldest historic site on campus. Students, alumni, and faculty at PVAMU regularly pay their respect to all internments of Wyatt Chapel.

Please! Visit the site! Pay some respect to the ancestors!

In several articles in the school newspaper, students exclaim that “there needs to be an understanding that while we are here doing what we are doing, there were others who came before us that worked diligently to produce the opportunities that we have at the present time.”

Our spirits within ourselves, which guide our dreams, visions, and actions, should be positively consistent with the spirits of those who came before us.

—Dr. Howard Jones and Kevin Washington

The disappointing fact, however, is that the Annual Slave Cemetery Trek ended sometime after the new millennium. In the 2000s, students picked up the beer cans, bottles, Styrofoam containers, and other trash, which served as “painful evidence of the lack of respect and understanding,” but most of the litter was piled up on the other side of a fence and remains hidden on the site. The burial ground sits on university-owned land, and PVAMU landscaping crews maintained the burial ground until recently, when the university contracted out the job to a private firm, which trims the grass a couple times each year.

Frank Jackson, the longtime mayor of the city of Prairie View, also led students across the soil of African slave roots in Waller County, "This is the same path that over 200 years ago was walked by 150 young African slaves.” As the students began the short journey to the wooden area of the hidden cemetery, some of them complained about the distance to the burial ground. Others backed away out of fear. "The total yardage of the cemetery is unknown," Jackson explained, "and the lives of the enslaved interments have been forgotten as if they never lived."

Wyatt Chapel cemetery is a great legacy that will allow future generations to understand their past.

—Frank Jackson

Lastly, Gregory Bevels, a former student and reporter for the Prairie View Panther, agreed with Jackson and exhorted, “Without the efforts of those individuals held as slaves, whose blood, sweat, and tears have been poured into the land we walk on each day, this university might not have become a reality. The individuals buried in the Wyatt Chapel cemetery are truly gone. What are the students and faculty of Prairie View A&M University going to do in order to make sure they are not forgotten?”

On one hand, Wyatt Chapel Community Cemetery is about the past buried in it, but it also has an innate orientation towards the future. The extant grave markers beckon us to read them and remember. They speak to the hopes of the formerly enslaved and their ancestors. Yet, the burial ground is an inherent site of transition — a gateway between past and present, life and death, material and spiritual, earth and heaven. Perhaps more than any other site on campus, it communicates the powerful communal and spiritual values that underscore the lived experiences of African Americans. The cemetery also tells the story of the university and its connection to plantation slavery, segregation, disfranchisement, and the struggle for racial equality.

One vision for Wyatt Chapel Community Cemetery is to leave much of what’s there intact, to edit the landscape and work with it. The decline of the cemetery is rooted in systemic racism, which limited the accumulation of black wealth and agency, and the cemetery’s restoration should reflect that history. It’s not about going back to what it looked like in 1921, at the time Rev. George Wyatt was most likely buried inside the metal fence enclosure. Rather, the restoration is about hope for the future. It’s about redressing the legacy of slavery, allowing the interments buried in unmarked graves and their descendants to speak for themselves—to educate and inspire the students still fighting for voting and civil rights in Waller County.

To realize this vision, a hybrid landscape would allow for a variety of treatments from maintaining what's there to newly created memorialization, which allows the cemetery to stay relevant over time. The trees noted in the Rice University study of the cemetery would serve as a new public entrance and undergo a useful transformation into an orchard, or a field for growing food — any sort of active use that would attract visitors. The main section would remain a prairie landscape, and the wilder parts further back would remain forested. At the end of a Texas winter, vines will blend into trees and create enclosed pathways in the rear sections of burial ground, retaining something of a Southern Gothic aesthetic. During warmer seasons, the trees will shade the paths, and the birds will sing, and you might even forget for a moment that you stand amidst the unmarked graves of slaves. Indeed, the wildest, most unkempt parts of the cemetery can also be the most sublime. Now, imagine other parts of Wyatt Chapel Community Cemetery fully restored to create a series of outdoor settings, complete with sculpture and monuments that recalibrate the center of institutional history at PVAMU as well as the local history of Waller County to include those who have too often been denied historical recognition.