Say My Name!

Searching for the Names of the Enslaved at PVAMU

In 2020, PVAMU President Ruth Simmons and Simmons Center for Race & Justice Director Melanye Price asked PVAMU History Professor Dr. Marco Robinson to begin conducting research into the early history of Prairie View A&M University. He asked a group of scholars in the Division of Social Sciences to conduct their own personal investigations and incorporate research projects into their American History survey courses. With no funding at his disposal, Dr. Robinson also worked with a newly-hired public historian, Dr. T. DeWayne Moore, and the PVAMU archivists–Phyllis Earles and Lisa Stafford–to write a series of grant proposals.

One of the most startling discoveries in the initial months was the fact that we did not know the name of a single person who had been enslaved on the plantation that later became PVAMU. Thus, we had no way to track down the descendants of the formerly enslaved people who lived at Alta Vista.

This blog post reveals the first name we discovered in 2021.

What’s in a Name?

For African Americans, the genealogical research process is painful. It reflects the blunt historical truth about hereditary chattel slavery. Historical researchers do not look for evidence about the existence of people. Instead, we need to trace the way property changed hands. Consider the documents associated with buying a house or vehicle in 2023. Slaves were considered property in the nineteenth century, and we can find records associated with slaves. But those records are in the owner’s name.

The 1850 and 1860 censuses included “slave schedules,” and the census enumerators asked slaveowners to list the ages and genders of the enslaved people they held in bondage. The slave schedules, however, do not include their names. This fact has made it difficult to track down the descendants of the people enslaved at Alta Vista.

Jared Ellison Kirby

Slaveowner, Planter, and Confederate Soldier

One of the first steps in the research process was examining the life of Jared Ellison Kirby, the slaveowner and planter who owned the land on which the university sits before the Civil War. An excellent place to learn more about the lives of Americans in the nineteenth century is Ancestry.com, the world’s largest collection of online family history records and government documents.

The slave schedules in the 1860 United States Census reveal that J. E. Kirby owned 159 slaves–more than any other slave owner in Austin County at that time.

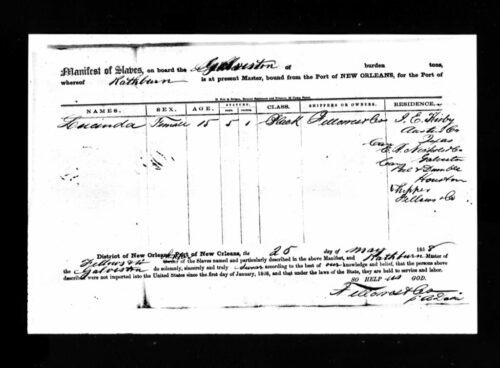

Besides census records and slave schedules, we located the manifest of the ship named Galveston, which transported slaves from New Orleans, Louisiana to Galveston, Texas in May 1858 for a domestic slave trading company, Fellows & Co.

Though an 1807 law banned the trans-Atlantic slave trade to the United States as of 1 January 1808, slaves could still be bought and sold (and transported) within the country. The same law that banned the foreign slave trade also regulated the internal transportation of slaves, requiring masters of vessels carrying slaves in coastal waters to provide a manifest detailing their slave cargo when leaving (“outward”) or entering (“inward”) a port.

The ship manifest contains the name of one person who likely lived at Kirby’s enslaved labor plantation, Alta Vista, in then-Austin County, Texas.

Slave Ship Galveston

In May 1858, Captain Rathburn transported a fifteen year-old woman, who was five feet, one inch tall, on the Galveston.

Her name was Lucinda.

Indeed, it will be very difficult to track down the descendants of people enslaved at Alta Vista, but the increased interest in university history and digital preservation has positively changed the prospects for institutional historians at PVAMU. If we try harder to make the archival collections at PVAMU available—and visible and searchable—online, and if white researchers who find evidence of slaveholding in their families will make family documents public, for Black researchers to access and use, we can discover the names of more enslaved people in Waller County.