Buried Legacies: How Racial Segregation Has Silenced HBCU Histories—and How Public History Can Speak Back

The significance and history of HBCU’s

HBCU’s were created to educate African Americans which during this time were majority enslaved or were refuse admissions into collegiate institutions.

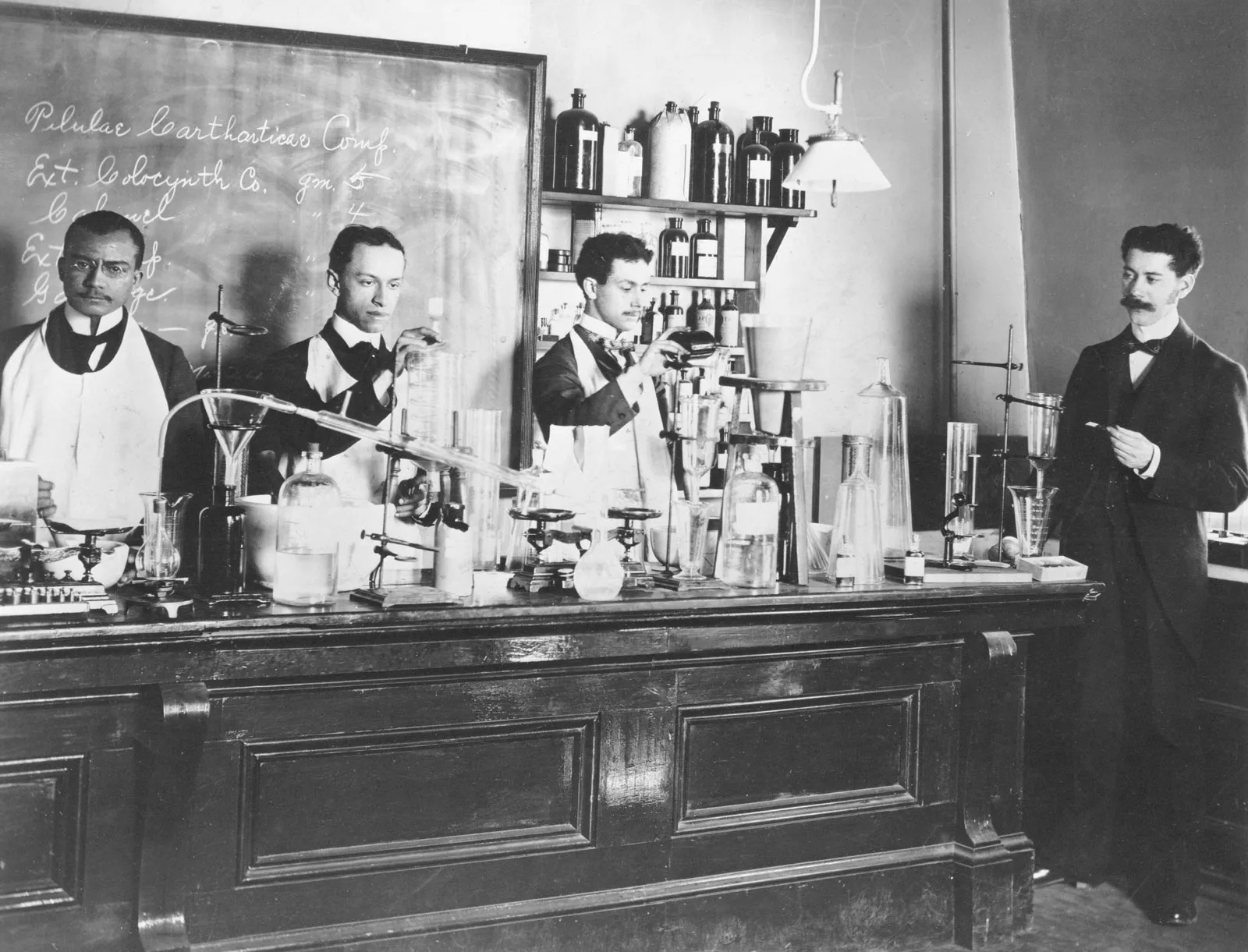

Across the landscape of American higher education, few institutions carry the weight of legacy, resilience, and resistance like Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs). Yet, despite their significance, many HBCUs continue to struggle against forces that have historically sought to silence or erase their institutional histories. Prairie View A&M University (PVAMU), the second-oldest public institution of higher learning in Texas, is no exception.

Erasure by Design; The Legacy of Segregation and Resource Hoarding

The effects of racial segregation have extended far beyond the classroom walls. At institutions like PVAMU, segregation wasn’t just about keeping Black students separate from white students—it was about controlling access to power, visibility, and historical legitimacy. Public funding disparities, limited archival preservation, and outright neglect have all contributed to the marginalization of PVAMU’s institutional memory.

For decades, the Texas A&M University System funneled resources disproportionately toward its flagship, Texas A&M University in College Station, while PVAMU—its HBCU counterpart—was often left underfunded and undervalued. This resource hoarding has tangible effects: deteriorating infrastructure, underfunded academic programs, and, critically, the slow erosion of institutional history. When there is no investment in archives, faculty research, or public memory projects, the stories that define a campus—and a people—fade into obscurity.

Invisible Histories, Missing Voices

The physical campus of PVAMU tells stories in whispers. Historical buildings go unmarked. Foundational figures remain unknown to current students. There’s no shortage of history here—just a shortage of support for telling it. How many students know that PVAMU was built on the grounds of a former slave plantation? Or that its founding was tied directly to Black Reconstruction politics? These are not footnotes; they are central to the American story.

How Pvamu can lead the way

• Establish a Public History Center: Create a dedicated space for researching, archiving, and sharing PVAMU’s past. This center could support oral histories, digital archives, and exhibitions that center Black agency and institutional legacy.

• Curriculum Integration: Embed PVAMU’s institutional history into general education courses. Let students learn about their own academic ancestors as part of their educational journey.

• Community Collaboration: Partner with local museums, libraries, and elders to preserve histories that exist beyond the campus gates. PVAMU is deeply tied to the surrounding Black communities—those stories deserve a spotlight too.

• Digital Desegregation: Use social media, podcasts, and digital storytelling to bring PVAMU’s history into wider public view. Accessibility is key to countering erasure.

• Student Involvement: Encourage students to become historians of their own institution. Through research projects, campus tours, and creative expression, students can transform memory into movement.