The Fundamental Connection Between Technology and Public History

How might technology enhances the production of public history?

As rising historians of the future, we are seen as metaphorical gatekeepers to the future . A public historians main purpose should surround aiding to its audience by advocating for the people connected to the surrounding communities. A common issue seen along the journey of evolution through public history is how to appeal to a large group of people, simultaneously while still impacting thier needs within the community. Technology is an impactful way to improve the community service we provide to the world by telling the stories of native people . Technology enhances public history by improving accessibility, engagement, and preservation. It enables the digitization of historical records, creating online archives and databases for wider access. Interactive tools like virtual tours and augmented reality offer immersive experiences, while social media and crowdsourcing allow public participation in historical research. Technology also aids in digital preservation, ensures secure storage, and facilitates collaboration among historians. Additionally, data analysis and visualization tools provide new insights and make complex information more understandable for the public.

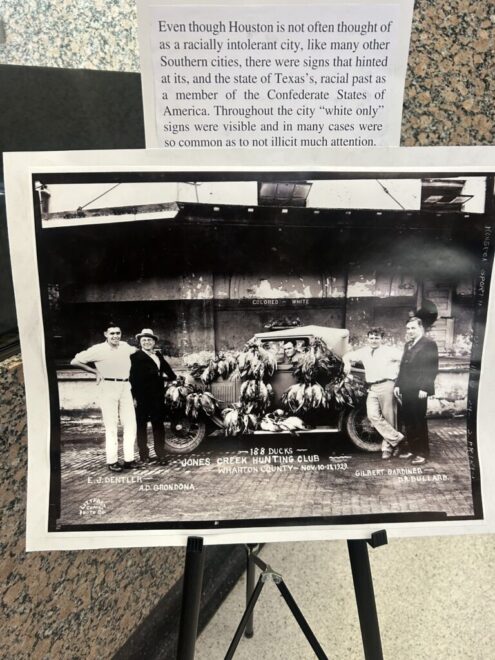

Jones Creek Hunting Club in Wharton County ( Nov, 10-11, 1929)

How can this be used in an everyday setting :

Technology can also play a crucial role in the production of public history by expanding access related to enhancing storytelling that may help adapt to community engagement. Digital tools allow historians to present historical narratives in interactive and immersive ways while also making history a more dynamic and accessible to its audience. Technologies such as Geographic Information Systems (GIS), virtual and augmented reality (VR/AR), and digital archives help visualize historical change, reconstruct lost environments, and provide new ways for the public to explore the past. Though , the effectiveness of these tools depends on addressing the research they ensures all communities can access and participate in these technological advancements.

Connection to Reading :

Andrew Hurley’s Chasing the Frontiers of Digital Technology: Public History Meets the Digital Divide underscores the growing role of technology in shaping public history. Digital tools such as Geographic Information Systems (GIS), virtual reality (VR), and interactive platforms have revolutionized how history is produced and consumed, making historical narratives more engaging, immersive, and accessible (1).However, Hurley also cautions that the “digital divide” can create barriers to participation, limiting the reach and inclusivity of these advancements (2).

One of the most engaging uses of technology in public history is its ability to create interactive and immersive experiences. GIS mapping projects enable users to visualize how places have changed over time, while VR and AR allow people to step into historical environments or witness past events as if they were there. Crowdsourced digital history projects, where the public contributes personal stories or historical artifacts, also foster engagement by making history a participatory experience. These technological innovations not only enhance historical understanding but also encourage communities to take an active role in preserving and interpreting their own histories.

Ultimately, Hurley suggests that while technology offers powerful tools for producing and disseminating public history, its effectiveness depends on equitable access and thoughtful implementation. If public historians address the digital divide and ensure that technology serves diverse communities, digital innovations can significantly enrich the way history is experienced and understood.

Notes(1):https://ncph.org/history-at-work/finding-the-intersection-of-technology-and-public-history/

Notes: (1) Andrew Hurley, “Chasing the Frontiers of Digital Technology: Public History Meets the Digital Divide,” The Public Historian 38:1 (February 2016): 3.

(2) Ibid, 12.

(3) Ibid, 18.